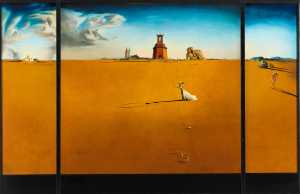

Giving form to images from the subconscious was an important motivation for the surrealists. They were inspired by Sigmund Freud's 'Traumdeutung' (interpretation of dreams) and psychoanalysis. Dalí compared the subconscious mind to having secret drawers, that could be opened at unexpected moments. He gave form to this idea in a contemporary version of the famous 'Venus de Milo'.

Specifications

| Title | Vénus de Milo aux tiroirs |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Bronze, paint and fur |

| Object type |

Sculpture

> Three-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Height 99 cm Depth 31,5 cm Width 29,5 cm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Artist:

Salvador Dalí

|

| Accession number | BEK 1467 (MK) |

| Credits | Purchased 1971 |

| Department | Modern Art |

| Acquisition date | 1971 |

| Creation date | in 1936 (1964) |

| Entitled parties | © Salvador Dalí, Fundación Gala-Salvador Dalí, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2022 |

| Provenance | Max Clarac-Sérou, Paris; Galerie du Dragon, Paris 1971 |

| Exhibitions | Tokyo 1964; Bern 1966; Tel Aviv 1966-1967; Humlebaek/Brussels 1967; Turin 1967-68; New York/Los Angeles/Chicago 1968; Rotterdam 1970-71; Stuttgart/Zurich/Humlebaek 1989-90; Rotterdam 1999; Barcelona/Madrid/St Petersburg 2004-05; London/Rotterdam/Bilbao 2007-08; Milan 2010-11; Frankfurt 2011; Rotterdam 2013-14a; Rotterdam 2017b |

| Internal exhibitions |

The Collection Enriched (2011) Een paraplu, een naaimachine en een ontleedtafel. Surrealisme à la Dalí in Rotterdam. (2013) De collectie als tijdmachine (2017) Collectie - surrealisme (2017) |

| External exhibitions |

Surreal Objects (2011) Dal nulla al sogno (2018) Dalí, Magritte, Man Ray and Surrealism. Highlights from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2023) Only the Marvelous is Beautiful (2022) Surrealist Art - Masterpieces from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2021) A Surreal Shock – Masterpieces from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2021) A Surreal Shock. Masterpieces from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2023) |

| Research |

Show research Digitising Contemporary Art Show research A dream collection - Surrealism in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

| Literature | New York/Los Angeles/Chicago 1968, pp. 145-46, fig. 217; Rotterdam 1970, cat. no. 188; Stuttgart/Zurich 1989, p. 207, cat. no. 158; Descharnes/Néret 1994, p. 279; Descharnes 1997, p. 199; Ades 2000, p. 117-18, fig. 24; R. Descharnes/N. Descharnes 2003, pp. 32-33, 36-37; Barcelona/Madrid/St Petersburg 2004-05, p. 148, fig. 244; Rotterdam/Barcelona/Madrid 2005, p. 243; London/Rotterdam/Bilbao 2007-08, pp. 20-21; Rotterdam 2007, pp. 94-95; Milan 2010-11, pp. 64-65; Frankfurt 2011, pp. 227-28, fig. p. 36; Paris/Madrid 2012-13, p. 190 |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Geographical origin | Spain > Southern Europe > Europe |

Entry catalogue Digitising Contemporary Art, A dream collection - Surrealism in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Author: Marijke Peyser

In the early 1920s Salvador Dalí discovered the writings of the Viennese psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Traumdeutung (1899-1900), in particular, made an overwhelming impression on him: [the work] presented itself to me as one of the capital discoveries of my life, and I was seized with a real vice of self-interpretation, not only of my dreams but of everything that happened to me, however accidental it might seem at first glance.’[1]

The classical statue of Venus appears to be made of plaster, but is actually bronze, painted white. Dalí made six openings in the trunk. In these rectangular voids he placed drawers with tufts of fur instead of knobs. In creating this alienating sculpture the artist had in mind ‘an allegory of psychoanalysis ... that shows the pleasure with which we embrace the many narcissistic smells that rise from all our drawers’.[2] Later Dalí added that the only difference between immortal Greece and our current age was Sigmund Freud. He had discovered that the human body ‘has countless secret drawers that can only be opened with the aid of psychoanalysis’.[3] Secret drawers are places where dreams, desires and obsessions, often of a sexual nature, are cherished, but also hidden. ‘This sculpture could cure us from psychoanalysis,’ said the artist.[4]

The subject of ‘woman with drawers’ recurs in many variations in his oeuvre. During a stay in London with his patron Edward James he drew and painted respectively City of Drawers and Le cabinet anthropomorphique (both in 1936).[5] On the cover Dalí designed for the Surrealist magazine Minotaure. Revue artistique et littéraire the minotaur’s chest is a half-opened drawer.[6] The figure on the cover of the catalogue for Dalí’s exhibition in the Julien Levy Gallery in New York (December 1936 – January 1937) has two breasts in the shape of concertinas with illustrations of the exhibited works. The two works on paper, Cannibalisme des tiroirs and Femmes aux tiroirs (both dating from 1937), are depictions of aggression and hate, against the background of the Spanish Civil War.

In 1929 André Breton asked his friends to think of ideas that could breathe new life into the group. Dalí’s suggestion, to make Surrealist objects, was published in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution.[7] In his short article Dalí described six different types of objects.[8] In his autobiography he described how he devoted himself to the promotion of the Surrealist object, his weapon against the dreams (les récits de rêve) and to automatic writing, both spearheads of Breton’s outlook in the first years of Surrealism: ‘The Surrealist object must be totally impractical and irrational. These Surrealist objects compete with useful and practical objects. In this violent struggle, which looks like a cockfight, the normal object will often come off worSt’[9] In May 1936 Breton put together Exposition surréaliste d’objets, a trail-blazing exhibition about Surrealist objects in Charles Ratton’s gallery in Paris. Dalí called it ‘the best Surrealist group manifestation ever’.[10]

Footnotes

[1] Gibson 1997b, p. 156. Freud’s writings were published in French in the 1920s and thus came to the attention of the Parisian Surrealists. A Spanish translation appeared in 1924.

[2] Descharnes/Néret 2005, p. 276.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Descharnes 1962, p. 164.

[5] Stuttgart/Zurich 1989, p. 202.

[6] Minotaure. Revue artistique et littéraire, 8 (1936).

[7] Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, 3 (December 1931).

[8] Ades 1995, pp. 151-52.

[9] Dalí 1952, pp. 347-48.

[10] See Gibson 1997b, pp. 409-10 for the names of the exhibitors.

All about the artist

Salvador Dalí

Figueras 1904 - Figueras 1989

Salvador Dali got to know the author André Breton - the founder of the surrealist movement - while he was studying in Madrid. In 1924, Breton wrote the first...

Bekijk het volledige profiel