This found sculpture looks almost like a modern totem pole in the centre of the city. The function of the wooden structure on a concrete base is unclear, but it acquires the status of a work of art in the photograph. Perhaps it was an ironic reference to the Statue of Liberty, the symbol of America. In 1920 Man Ray sent the photograph, printed as a postcard, to Tristan Tzara as a contribution for his compilation ‘Dadaglobe’. Theo van Doesburg acquired the photograph in 1921.

Specifications

| Title | La plus belle statue d'Amérique |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Gelatine silver print on fibre-based paper |

| Object type |

Photograph

> Two-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Height 11,4 cm Width 8,7 cm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Artist:

Man Ray

|

| Accession number | 3501 (MK) |

| Credits | Purchased with the support of Mondriaan Fund, 2002 |

| Department | Modern Art |

| Acquisition date | 2002 |

| Creation date | in 1920 |

| Entitled parties | © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2018 |

| Provenance | Tristan Tzara, Paris 1920; Theo van Doesburg, 1921-31; Nelly van Doesburg-van Moorsel, 1931-75; Wies van Moorsel, Amsterdam 1975-2002 |

| Exhibitions | Drachten 1998; Rotterdam 2014b; New York 2016 |

| Internal exhibitions |

Surreëel: foto's uit de collectie van Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2011) |

| External exhibitions |

Dadaglobe Reconstructed (2016) Dal nulla al sogno (2018) Surrealist Art - Masterpieces from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2021) A Surreal Shock – Masterpieces from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2021) Only the Marvelous is Beautiful (2022) Dalí, Magritte, Man Ray and Surrealism. Highlights from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2023) A Surreal Shock. Masterpieces from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (2023) |

| Research |

Show research A dream collection - Surrealism in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

| Literature | Rotterdam 2014, pp. 200, 203, cat. no. 39c |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Technique |

Gelatine silver print

> Bromide print

> Photographic printing technique

> Mechanical

> Planographic printing

> Printing technique

> Technique

> Material and technique

|

Do you have corrections or additional information about this work? Please, send us a message

Entry catalogue A dream collection - Surrealism in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Author: Marijke Peyser

Dada started in Zurich in 1916 and quickly spread to other European cities. In 1920 and 1921 the movement reached its peak in Paris. Artists who joined the movement protested vehemently against the havoc wrought by the First World War. In 1918 the Romanian avant-garde poet and writer Tristan Tzara published his ideas and objectives in the Dada Manifesto. Dada’s principal objective was to free art from the prevailing standards about what art ought to be and eliminate the boundaries between the different art disciplines. Dada artists expressed themselves through art forms that rejected the rational: their art was absurd and playful, confrontational and nihilistic, intuitive and emotional. It was ‘anti-art’. Elements of language and sound or noise frequently played a major role.

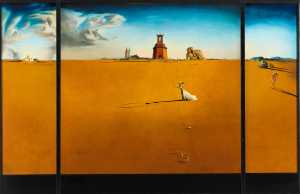

Dada took off in New York in the early 1920s thanks to the ideas and activities of Francis Picabia, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray.[1] Man Ray’s photographs La mer de merde and La plus belle statue d’Amérique of 1920 are typical Dada works. La mer de merde is a photograph of a well-used painter’s palette with thick blobs of paint. It refers to traditional painting, an art form Man Ray had abandoned at that time.[2] La plus belle statue d’Amérique is a black-and-white photograph of a vertical wooden structure on a concrete plinth. The surroundings of this ‘monument’ are indefinable. That the photograph was taken in the United States is confirmed by the flag that flutters on top of the building on the right. The function of this found object is unclear but in the photograph it is given the status of an artwork.

In 1919 Tzara moved to Paris. His fruitful contacts with André Breton and his companions gave a great boost to Dada. They regarded the writers the Comte de Lautréamont and Alfred Jarry as pioneers of the movement.[3] The renewed interest in Jarry’s much-discussed stage play UBU ROI that caused an enormous scandal in 1896 and was only performed twice can also be seen in this context.[4] A new production was prepared of the absurdist work, which poked fun at society, law and order and was peppered with scatological catchphrases. The narrative began with ‘le mot magique’, merde, which was repeated thirty-three times in the course of the performance, then pronounced as ‘merdre’. Like Jarry, Man Ray used the word merde in a word game and placed it on the painter’s palette which became obsolete in avant-garde art.

La mer de merde and La plus belle statue d’Amérique were intended for publication in Dadaglobe which Tzara started in 1920. His plan was to ask fifty Dada artists for a contribution in text and/or image. A list of contributors from a great many countries was published in the first and only edition of the magazine New York Dada, which Duchamp and Man Ray published in 1921.[5] Tzara also approached I.K. Bonset (pseudonym of Theo van Doesburg) to make a contribution. Van Doesburg offered four texts for publication in Dadaglobe.[6] Tzara tried to achieve between 160 and 200 pages and a print run of 10,000 copies, aside from deluxe editions.[7] Man Ray was one of the contributors from New York. Unfortunately the long-prepared publication of Dadaglobe came to nothing.[8] Nevertheless Tzara and Van Doesburg continued their correspondence.

On 21 June 1921 Van Doesburg asked Tzara if he would work with him on his publication Mécano: ‘I await your news with impatience. And your contributions to MECHANO [sic].’[9] On 9 October 1921 Van Doesburg received a positive answer from Tzara: ‘Today I am sending you three reproductions by Man Ray, two by Charchoune … All for Mechano [sic].’[10] Van Doesburg replied on 25 October 1921: ‘Mechano [sic] comes out this month and I intend to publish everything you sent me. I was delighted to make the acquaintance of Mr Man Ray’s work.’[11] These photographs by Man Ray, once intended for Dadaglobe, probably came into Tzara’s possession.[12] Since Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen bought these photographs from Nelly van Doesburg’s estate, Theo van Doesburg must have got hold of them at some time. However they were not published in Mécano. Three other works by Man Ray were published in two issues of Mécano in 1922, including Ballet, a 1918 aerograph, which is now known as The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows.[13]

Footnotes

[1] See Baker 2007, p. 164, for Man Ray’s explanation: ‘In 1919 [sic 1921] with the permission and with the approval of the other Dadaists I legalized Dada in New York.’

[2] Traditional painting featured throughout Man Ray’s oeuvre: painting was his great love. In his Dada period Man Ray experimented with other media.

[3] Peterson 2001, p. 34: In 1919 André Breton wrote in a letter to Tzara that he regarded Jarry as a genius comparable with Rimbaud and De Lautréamont. Tzara declared that he saw Jarry as a pioneer of Dada.

[4] Ibid., pp. 34-35.

[5] Ades 2006, p. 159.

[6] See Tuijn 2003, pp. 150-51, for the letter of 3 January 1921, in which Tristan Tzara asked the Dutchman to work with him on Dadaglobe. A registered package dated 18 January 1921 with documents for Dadaglobe was sent to Tzara; Entrop 1988, p. 25.

[7] Entrop 1988, p. 25.

[8] See Huelsenbeck/Sheppard 1982, pp. 5-82.

[9] Tuijn 2003, p. 153.

[10] Ibid., p. 165.

[11] Ibid., p. 167.

[12] Email from the art historian Adrian Sudhalter to Margreet Wafelbakker (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen), 14 July 2010: ‘These prints [Man Ray’s] were likely sent from Man Ray to Tzara with his December 1, 1921 letter [which mentions enclosed photographs for Dadaglobe] or hand delivered to Tzara the following week by Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia on behalf of Man Ray.’

[13] Information from copies of the magazine Mécano.

All about the artist

Man Ray

Philadelphia 1890 - Parijs 1976

The American artist Emmanuel Radnitzky, who would call himself Man Ray, began his career as engraver and advertising designer. In New York he got to know the...

Bekijk het volledige profiel