Specifications

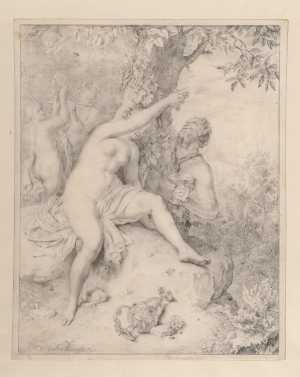

| Title | Leda and the Swan |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Black chalk, pen and brown ink |

| Object type |

Drawing

> Two-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Height 128 mm Width 109 mm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Draughtsman:

Leonardo da Vinci

|

| Accession number | I 466 (PK) |

| Credits | Loan Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (former Koenigs collection), 1940 |

| Department | Drawings & Prints |

| Acquisition date | 1940 |

| Creation date | in circa 1505-1507 |

| Watermark | none (vH, 4P) |

| Inscriptions | 'Lionardo da Vinci' (lower right, pen and brown ink) |

| Collector | Collector / Franz Koenigs |

| Mark | T. Lawrence (L.2445), F.W. Koenigs (L.1023a on the removed backing sheet) |

| Provenance | William Young Ottley (1771-1836, L.2642, L.2662, L.2663, L.2664, L.2665 desunt), London; his sale, London (Philipe) 06-23.06.1814, lot 1411 (BP 18/10/0); Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830, L. 2445/2446), London; art dealer Samuel Woodburn (1781-1853, L.2584), London 1836a, fifth exhibition, no. 58; The Prince of Orange, afterwards King William II of the Netherlands (1792-1849), The Hague, acquired in 1840; his sale, The Hague (De Vries, Roos, Brondgeest) 12.08.1850, probably part of lot 262 (bought in); his daughter Princess Sophie van Oranje-Nassau (1824-1897), Grand Duchess von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, Weimar; her husband Grand Duke Karl Alexander von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1818-1901) Weimar; their grandson Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1876-1923), Weimar; Art dealer Julius W. Böhler (1883-1966), Lucerne; Franz W. Koenigs (1881-1941, L.1023a), Haarlem, acquired in 1929 (School of Leonardo, corrected to Leonardo da Vinci); D.G. van Beuningen (1877-1955), Rotterdam, acquired with the Koenigs Collection in 1940 and donated to Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

| Exhibitions | London 1834-36, 5th exh, no. 58; Amsterdam 1934, no. 571; Paris 1935, no. 573; Los Angeles 1949, no. 81; Paris 1952, no. 6; Florence 1952, no. 54; Rotterdam 1952, no. 90; Paris/Rotterdam/Haarlem 1962, no. 49; Londen 1989, no. 14; Rotterdam 1995, p. 206; Rotterdam 1997-1998; Damish 1997, no cat.; Florence 2000, no. 1; New York 2003, no. 98; Paris 2003, pp. 257, 289, 292, 301-304, 308, no. 105; Rotterdam 2010 (coll 2 kw 6); St Petersburg/Dordrecht/Luxembourg 2014, pp. 290-291; Haarlem 2018, p. 176, no. 55; Paris 2019, pp. 292, 421, no. 147 |

| Internal exhibitions |

Rondom Raphaël (1997) Tekeningen uit eigen bezit, 1400-1800 (1952) Italiaanse tekeningen in Nederlands bezit (1962) De Collectie Twee - wissel VI, Prenten & Tekeningen (2010) |

| External exhibitions |

Leonardo. Expressie en Emotie (2018) Leonardo da Vinci (2019) |

| Research |

Show research Italian Drawings 1400-1600 |

| Literature | Ottley 1823, p. 20, pl 18 (Leonardo, c. 1480-1500 in Milan); London 1834-36, 5th exh, no. 58; Von Ritgen 1865, nr. 32 (Leonardo da Vinci), ill.; Morelli 1890, p. 196. ill. (attrib. Sodoma); Morelli 1900, pp. 154-157 (Sodoma); Gronau 1902, p. 148; Berenson 1903, no. 1020A; Frizzoni 1905, p. 66; Von Seidlitz 1909, vol 2, p. 131 (kopie); Poggi 1919, p. 58, fig. 112; Venturi 1920, p. 136, ill. 125, (copy); Carotti 1921, p. 85; De Toni 1922, p. 115, fig. 31; De Rinaldis 1926, pp. 222-223 (not Leonardo); Popp 1928, p. 50, ill. 61; Sirén 1928, vol. I, p. 157, vol. III, ill. 195A; Suida 1929, pp. 158, 274; Bodmer 1931, pp. 329, 417, ill.; Amsterdam 1934, no. 571, ill.; Paris 1935, no. 573; Berenson 1938, vol. I, p. 180 (no. 5) vol. II, p. 112 (no. 1020A), vol. III, ill. 546; Hannema 1942, ill.; De Tolnay 1943 (1972), no. 69, ill.; Giglioli 1944, pp. 125-126 (not Leonardo); Popham 1945, no. 208, ill.; Goldscheider 1948, p. 30, no. 56, ill; Los Angeles 1949, nr. 81, ill.; Paris 1952, no. 6, pl. 2; Florence 1952, no. 54; Rotterdam 1952, no. 90; Castelfranco 1954, fig. 14, pl. 170; Heydenreich 1954, vol. I, pp. 54, 184, vol. II, p. 54, ill. 66; Haverkamp Begemann 1957, no. 40, pl. 36, ill.; Goldscheider 1959, pp. 158-159 under pl. 36; Rosenberg 1959, p. 29, fig. 61; Zeri 1959, p. 42, fig. 28b; Berenson 1961, vol. I, p. 262, vol. II, p. 213, vol. III, no. 1082cI, fig. 513; Paris/Rotterdam/Haarlem 1962, no. 49, pl. 38; Wallace 1966, p. 160, ill.; Clark 1967, pp. 116-117; Ottino Della Chiesa 1967, p. 107, under no. 34 (ill.); Clark 1969, pp. 18-19, 22, ill. 18; Clark/Pedretti 1968-69, vol. 1, p. 33, under no. 1237; Wasserman 1969, p. 130; Forlani Tempesti 1970, p. 66, fig. 11; Pedretti 1973, pp. 98, 125, ill. 101; Washington 1973, p. 450, n. 5, under no. 162; Allison 1974, pp. 375-376, ill. 2; Brown/Seymour 1974, pp. 130-131, fig. 3; Weil-Garris Posner 1974, pp. 33-34, fig. 32; Gould 1975, pp. 117-118, fig. 59; Rosci 1976, pp. 137 (ill.), 154; Clark 1979, p. 12, ill. 6; Pedretti 1979, no. 39; Keele/Pedretti 1979-80, vol. 2, p. 835; Kemp/Smart 1980, pp. 160-171; Pedretti 1982, no. 39; Vezzosi in Vinci 1982, p. 21, fig. 96; Tanaka 1983, pl. 65; Vezzosi in Naples/Rome 1983-84, pp. 90-91, ill. 127 and plate XXIV; Ames-Lewis/Wright 1983, p. 216, fig. 45a; Calvesi 1985, p. 139, ill.; Ames-Lewis 1989, pp. 74-76, fig. 5; Hochstetler Meyer/Glover 1989, p. 80, ill. 9; Kemp/Roberts 1989, p. 65, no. 14; Hinterding/Horsch 1989, p. 53; Londen 1989, no. 14, ill.; Hochsteler Meyer 1990, pp. 279-280, ill. 2, p. 284; Nathan 1990, pp. 52, 57, no. 21, ill. 18; Dalli Regoli 1991, pp. 6, 14, ill. 2; Zeri 1991, p. 179, fig. 269; Marani 1992, p. 19, ill. 13; Pedretti 1993, p. 188; Elen 1993, p. 207; Popham 1994, no. 208; Jaffé 1994, p. 165 under no. 880; Marani 1995, p. 220, fig. 47; Rotterdam 1995, p. 206; Clayton 1996-97, p. 76; Pedretti 1996, p. 63, fig. 6; Ames-Lewis 1997, pp. 119, 121, fig. 4; Pedretti 1997, pp. 258-259, fig. 1-3, 5; Arasse 1997-1998, pp. 422, 425, fig. 281; Vecce 1998, pp. 255-256; Marani 1999, p. 270, ill.; Van der Windt in Florence 2000, no. 1, ill.; Marani 2000, pp. 264, 270, ill.; Franklin 2001, p. 36, ill. 23 (Bachiacca); Nanni in Vinci 2001, pp. 36-37, ill. 18; Testaferrata in Vinci 2002, pp. 112-113, no. 2.4 (facsimile); Lehmann 2001, pp. 94-95, fig. 4; Laurenza 2001, pp. 88-89, fig. 67; Clayton 2002-2003, pp. 150, 152, no. 1 under no. 58; Zöllner 2003, p. 289, ill. 57; Bambach in New York 2003, pp. 53-56, nr. 98, ill; Bambach in Paris 2003, pp. 301-304, no. 105, ill.; Clayton in Ottawa 2005, pp. 64-65, ill. 2.2; Dalli Regoli 2006a, pp. 75-76, ill (incorrect caption); Marani 2003, p. 477 (fig. 6); Marchesi 2005, passim, fig. 1-6; Dalli Regoli 2006b, p. 118, fig. 1 (engraving), p. 123; Geronimus 2006, p. 258, fig. 199; Kemp 2006, p. 264; Lange Malmanger 2006, pp. 107-108, fig. 2; Natali 2007, p. 193, fig. 102, pp. 204-205, fig. 115; Nelson 2007, p. 6, fig. 3 (engraving); Starnazzi 2008, pp. 109, 111, ill.; Marani 2010, p. 175, fig. 30; Budapest 2009-2010, p. 270 under no. 68 (as inspiration for Raphael’s Esterházy Madonna); Clayton 2012, pp. 22-24, under no. 3, fig. 10; Ilsink 2012, pp. 21-22, fig. 6, 7; St Petersburg/Dordrecht/Luxembourg 2014, pp. 290-291, ill.; Brown 2015, p. 177, n. 80; Fiorio 2015, p. 546 (under nos IV. 63, IV 64); Geronimus in Washington 2015, pp. 175, 177, no. 5; Marani 2015, p. 138, fig. 9; Isaacson 2017, p. 328, fig. 82; Haarlem 2018, p. 176, no. 55; Clayton 2018, pp. 94-95, fig. 13; Bambach 2019, vol. 2, pp. 446, 448-451, ill. 8.91, vol. 4, p. 296, no. 494; Kemp 2019, p. 156, ill.; Paris 2019, pp. 292, 421, nr. 147, ill.; Marani 2019, pp. 262, 264, ill.; Quiviger 2019, p. 131 (incorrect illustration); Salvi 2019, pp. 40-41; Zöllner 2019, p. 294, ill. 57; Forcellino 2019, pp. 214-215, 321 (under no. 3.3); Taglialagamba 2019, pp. 309-312 (under no. 3.1), ill. 2b.; Amboise 2023, p. 32, fig. 10 |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Geographical origin | Italy > Southern Europe > Europe |

Do you have corrections or additional information about this work? Please, send us a message