Auguste Rodin is generally regarded as the founder of modern sculpture and the most influential sculptor of the nineteenth century. For him, depicting movement and life force was the essence of sculpture. In this respect, the human body was an inexhaustible source of inspiration.

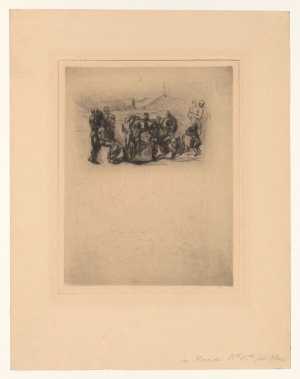

However, Rodin did not have an easy start as a young artist. Rejected by the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, Rodin instead attended the Petit École, which specialised in the applied arts. His sculptures were rejected by the Paris Salon, the most important stat-organised, annual art exhibition organised, for being too realistic. Rodin’s first success came in 1880, at the age of forty, when he was commissioned to design the doors for the planned Musée des Arts Décoratifs, which was ultimately never built. Inspired by the ‘Inferno’ section of Dante’s epic poem the Divine Comedy, Rodin designed ‘The Gates of Hell’ as a bronze entrance to the museum. But his ambition turned out to be too great and he was unable to complete the assignment. It became his life’s work: many of his famous individual sculptures, such as ‘The Thinker’ and ‘The Kiss’ originated as details of ‘The Gates of Hell’. Only after his death was the unfinished work cast in bronze.

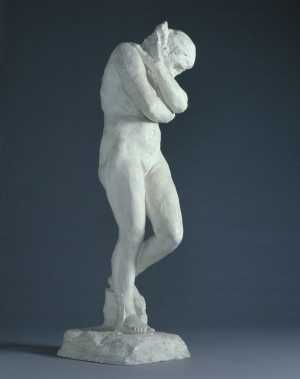

During a trip through Italy, Rodin became acquainted with the sculptures of Michelangelo (1475-1564), which made a deep impression on him. He was especially taken by the half-finished pieces, in which the figures seem to wrest themselves from their marble blocks. The suggestion of movement and the expression of emotion in the figures’ postures were lessons that Rodin applied in his own work. But unlike Michelangelo, Rodin preferred plaster or clay, materials in which he could model freely and play with the structure of the surface before having the result cast in bronze. The deliberately rough, unfinished ‘skin’ gives his sculptures a more realistic, human quality that contrasts with the idealised bodies of classical sculptures.

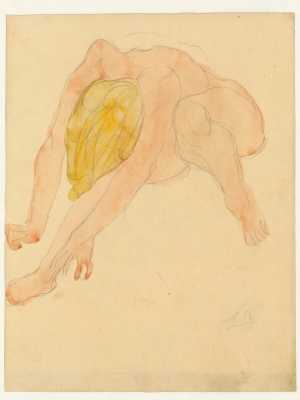

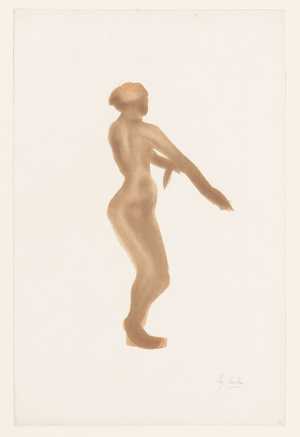

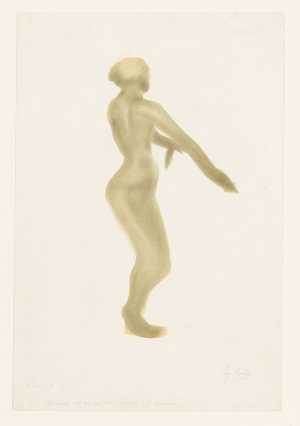

Movement is an essential characteristic in Rodin’s work. Just as the Impressionists wanted to capture the movement of light with paint on canvas, Rodin strove to express dynamism in bronze. For him, movement was the essence of life and the human body was an inexhaustible source of inspiration for representing life force.

He deployed muscle mass, twisted postures and expressive gestures to depict emotions, usually not referring to strength or heroism, but rather to fear or vulnerability. His ambition to give the most convincing form possible to a movement or emotion sometimes led to radical solutions. For example, Rodin did not hesitate to omit parts of the body, or to isolate them as a stand-alone work, if it benefitted the expression of the sculpture. An example of this is the omission of the head in ‘The Walking Man’ - a bronze cast of which is displayed on the Westersingel in Rotterdam - so as not to divert attention from the striding movement.

Rodin did not achieve international fame until 1900. In that year, he exhibited his work in his own pavilion opposite the ‘Exposition Universelle’ in Paris, a bold move that instantly established his name with the general public. The year before, in 1899, he had an exhibition at the Rotterdamsche Kunstkring, which then travelled to Amsterdam and The Hague. After the show, the Rotterdam harbour administrator Jan Hudig purchased a monumental plaster cast of ‘Eva’ as a gift for Museum Boymans: the first Rodin in a Dutch museum collection. In 1939, the museum’s director Dirk Hannema acquired one of the three original bronze studies of ‘Pierre de Wissant’ from Rodin’s bronze founder, Rudier.

Auguste Rodin

Parijs 1840 - Meudon 1917