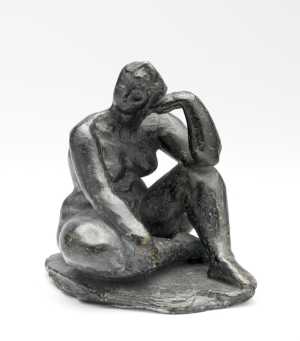

Charlotte van Pallandt occupies an exceptional position as one of the few female artists in a world of sculpture dominated by men. She was greatly inspired by Aristide Maillol (1861-1944), but unlike his idealised sculptures of women, Van Pallandt’s figures have a lively and individual character. This ability to imbue a sculpture with personality made her a popular portraitist.

Becoming an artist was a far from obvious choice. Born Charlotte Dorothée, Baroness van Pallandt, she grew up in an aristocratic milieu, and her education was provided by French governesses, English boarding schools and piano and drawing lessons. Although she enjoyed drawing and exhibited talent at an early age, she was told that the life of an artist was unsuitable for a woman of her class. It was only at the age of twenty-five, after leaving her husband after four unhappy years of marriage, that she was free to devote herself seriously to making art.

Van Pallandt found her teachers in Paris, where she first took painting lessons with the Cubist painter André Lhote (1885-1962). An encounter with the Franco-Russian sculptor Akop Gurdjan (1881-1948) set her on the path towards sculpture. In 1935, after several years of experimenting with this art form in the Netherlands, she returned to Paris. She took classes at the Académie Ranson with the sculptor Charles Malfray (1887-1940), who had succeeded Maillol five years earlier upon the latter’s recommendation. Van Pallandt said that Malfray taught her ‘to compose in the third dimension’, to approach a sculpture as an interplay of planes, volumes and the lines between them. Only then could one arrive at a model for the desired figurative form. Van Pallandt’s sculptures of human figures consequently have a structure based on geometric volumes.

She shared this architectural approach with Maillol. When she visited him in his studio in 1939, when Maillol was close to eighty, that was exactly the message he gave her: ‘When you make a sculpture, you start from the triangle, the square or the circle.’ She followed this advice in making the monumental statue of Queen Wilhelmina, which was unveiled in Rotterdam in 1968 and is perhaps her most famous work. The monarch in her long fur cloak has become an unyielding triangle, leaning slightly backwards.

During the Second World War, Van Pallandt returned to the Netherlands and became acquainted with Truus Trompert, a model in Amsterdam with whom she would work for more than twenty years. There are numerous small sculptures of her in spontaneous, quickly modelled poses. In contrast to Van Pallandt’s earlier, more stately figures, these sculptures are lively and full of character. Van Pallandt: ‘There is a frolicsome quality to the sculptures of Truus, something slender and rising, the movement of living and breathing.’ Only a few were later worked out in large format, including ‘Seated Nude With Apple’ in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

It was for her portraits that Van Pallandt gained the most appreciation. She succeeded in capturing the character of all her models, whether they were writer and artist friends or Queen Juliana. Despite her late start - she was already over fifty when she began to exhibit frequently - Van Pallandt acquired a prominent place in Dutch sculpture. She continued to work into old age: ‘I bade adieu to the mundane life and knew I would spend the rest of my time on art. I had to.’

Charlotte van Pallandt

Arnhem 1898 - Noordwijk 1997