Seeing & doing

10 results

To do

View archiveBefore & after your visit

Restaurant Renilde

The depot has a (literally) glistening exterior and a spectacular interior. Another special experience awaits visitors who take the express lift to the sixth floor. The depot’s roof not only provides a spectacular panoramic view of the city, but it also has a a restaurant, named Renilde, beautifully situated in a green oasis. And all of this in the heart of Rotterdam!

More about Renilde

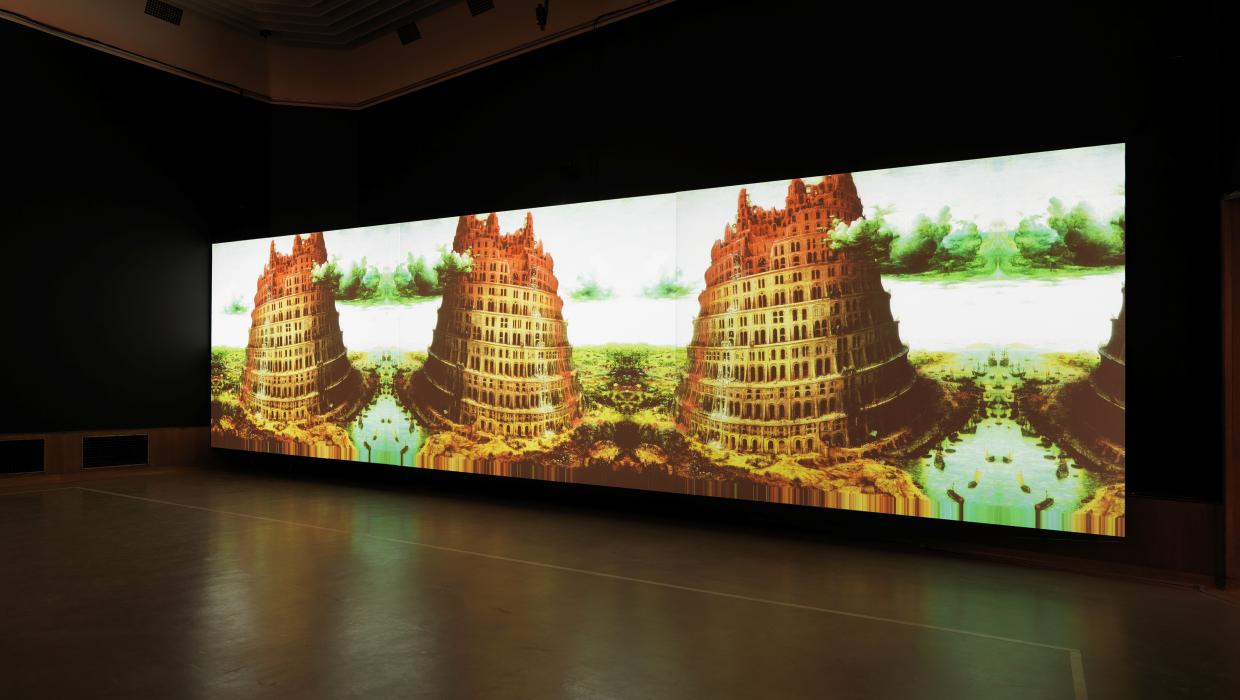

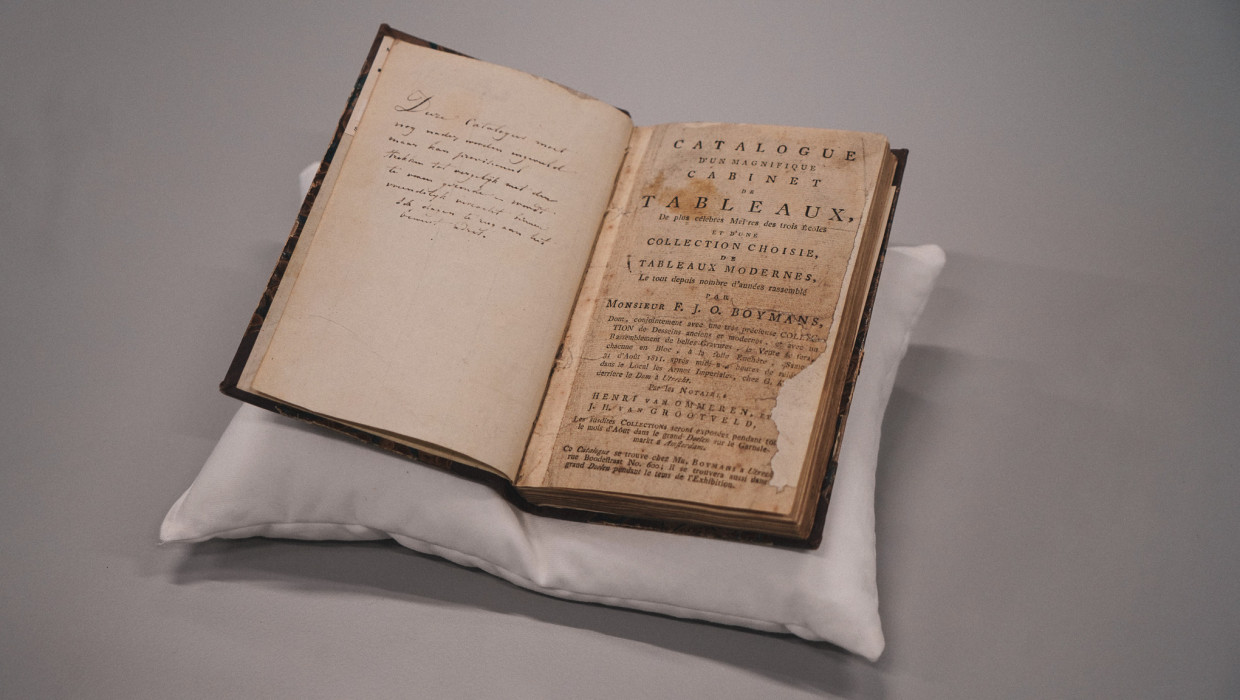

The Boijmans Collection Online

There are thousands of artworks on Boijmans Collection Online. The museum takes you on a journey through the history of art.

View the online collection