Specifications

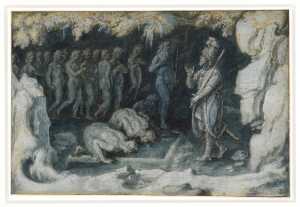

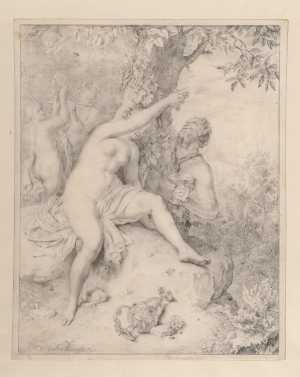

| Title | Four Studies of a Female Nude, an Annunciation and Two Studies of a Woman Swimming |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Pen and ink on parchment |

| Object type |

Drawing

> Two-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Height 223 mm Width 167 mm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Draughtsman:

Pisanello (Antonio di Puccio Pisano)

|

| Accession number | I 520 recto (PK) |

| Credits | Loan Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (former Koenigs collection), 1940 |

| Department | Drawings & Prints |

| Acquisition date | 1940 |

| Creation date | in circa 1431-1432 |

| Inscriptions | 'Simonum Memmius Senens[iu]m' (below right, pen and brown ink), '1' en '1' (verso, below right, pencil) |

| Collector | Collector / Franz Koenigs |

| Provenance | Count Moriz von Fries (1777-1826, L.2903), Vienna, until c. 1820, to mr. W. Mellish, London; Marquis de Lagoy (1764-1829, L.1710)***, Aix-en-Provence; - ; Franz W. Koenigs (1881-1941, L.1023a), Haarlem, acquired in 1930 (Sienese School, 14th century, corrected to Pisanello); D.G. van Beuningen (1877-1955), Rotterdam, acquired with the Koenigs Collection in 1940 and donated to Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

| Exhibitions | Paris 1932, no. 90; Amsterdam 1934, no. 611; Paris 1935, no. 646; Paris 1952, no. 1; Rotterdam 1952, no. 76; Rotterdam 1957, no. 33; Paris/Rotterdam/Haarlem 1962, no. 8; Venice/Florence 1985, no. 7; Rome 1988, no. 45 (verso); Rotterdam/New York 1990, no. 53; Moskow 1995-1996, no. 22; Paris/Verona 1996, no. 41; Rotterdam 2009 (coll 2 kw 1); Los Angeles 2018, no. 62 |

| Internal exhibitions |

Tekeningen uit eigen bezit, 1400-1800 (1952) Italiaanse tekeningen in Nederlands bezit (1962) Van Pisanello tot Cézanne (1992) De Collectie Twee - wissel I, Prenten & Tekeningen (2009) |

| External exhibitions |

The Renaissance Nude, 1400-1530 (2018) |

| Research |

Show research Italian Drawings 1400-1600 |

| Literature | De Hevesy 1932, p. 148, p. 151, ill.; Paris 1932, no. 90; Amsterdam 1934, no. 611; Van Schendel 1934, p. 243, ill.; Venturi 1934, p. 494; Paris 1935, no. 646; Degenhart 1941, pp. 24, 27, 50, 65, fig. 26; Degenhart 1945, pp. 21-22, 30, 49, 72, fig. 26; Arslan 1948, p. 288, n. 2; Degenhart 1949, p. 16, fig. 11; Deusch 1943, pp. 12, 42, ill. 2; Paris 1952, no. 1, pl. 1; Cain/Vallery-Radot 1952, ill.; Haverkamp Begemann 1952, no. 76; Dell’Acqua 1952, p. 10, pl. 2; Haverkamp Begemann 1957, no. 33, ill.; Verona 1958, under no. 95; Coletti 1958, pl. 6; Chiarelli 1958, pp. 29-30; Rosenberg 1959, p. 7, pl. 14; Bean 1960, under no. 223; Degenhart/Schmitt 1960, p. 75 fig. 24, pp. 112, 116-117 fig. 86, 120-21 n. 5, 129 n. 20, pl. 86-88; Schuler/Hänsler 1962, pp. 34-35; Sindona 1962, pp. 60, 129, ill. 13; Paris/Rotterdam/Haarlem 1962, no. 8, pl. 9; Fossi Todorow 1962, pp. 135, 138 139, ill. 2; Vienna 1962, p. 267 under no. 279; Degenhart 1963, pl. 332; Edschmid 1963, p. 149, ill.; Fossi Todorow 1966, pp. 19, 20, 47, 57-8, no. 2 (recto), p. 137, no. 202 (verso) pl. 2; Magagnato 1966, pp. 292, 294-95; Byam Shaw 1967, p. 45, ill. 2; Degenhart/Schmitt 1968, vol. I-2, p. 641 (Pisanello); Baxandall 1972, p. 78; Chiarelli/Dell'Acqua 1972, no. 15, pl. 5; Anzelewsky 1972, p. 251, no. 157; Paccagnini 1972, p. 148, ill. 105; Byam Shaw 1978, no. 7, ill.; Meder/Ames 1978, vol. 1, p. 303, vol. 2, p. 15, ill. 12; Panczenko 1980, p. 21, fig. 19; Maiskaia 1981, p. 92, fig. 42; Pignatti 1981a, pp. 72-73; Christiansen 1982, p. 148; Panczenko 1983, pp. 54, 59, fig. 53; Aikema/Meijer 1985, no. 7, ill.; Ruggeri 1985, p. 235; Byam Shaw 1985, p. 832; Himmelmann 1985, p. 25, n. 40, ill. 39; Bober/Rubinstein 1986, p. 179 under no. 142; Macioce 1989, p. 39; Rome 1988, no. 45, ill. (verso); Degenhart/Schmitt 1990, vol. II-6, p. 477, n. 9 (Pisanello); Luijten/Meij 1990, no. 53, ill., fig. d; De Marchi 1992, p. 203, 215, n. 109; De Marchi 1992a, p. 11; Bernstein 1992, pp. 49-50; Ter Molen 1993, pp. 86-87, ill.; Degenhart/Schmitt/Eberhardt et al. 1995, pp. 79, 96, 104, 108, 113, 280 n. 37, fig. 113; Elen 1995, under no. 15; Cordellier 1995, p. 114 (recto); Moscow 1995-1996, no. 22, ill., pl. on p. 39; Ventura 1996, pp. 16-17, ill.; Filippi 1996, pp. 205-09, ill.; Paris/Verona 1996, no. 41; London 2001, pp. 198-199, 201-202, fig. 5.8; Degenhart/Schmitt 2004, vol III-2, pp. 149, 151-53, 156, 163, 214, 231 fig. 166e, 234, 236, 238-40, 266, 268-70, 335, 386-7, fig. 303b, 471-80, 489, no. 764 and under no. 746, pl. 76, 77, fig. 364, 367 369 (workshop Pisanello); Hiller von Gaertringen 2008, p. 196; London/Florence 2010, pp. 62-63, ill. 45; Bohn 2012, pp. 42, 67 n. 75; Cadogan 2012, pp. 201-02; Korbacher 2012, p. 79, 84; Los Angeles 2018, no. 62, ill. |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Geographical origin | Italy > Southern Europe > Europe |

Do you have corrections or additional information about this work? Please, send us a message