Specifications

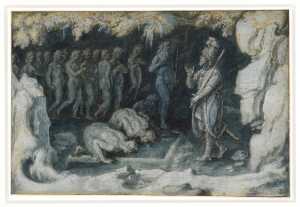

| Title | The Labourers in the Vineyard |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Brush and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white, on brown-ochre prepared paper |

| Object type |

Drawing

> Two-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Height 296 mm Width 445 mm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Copy after:

Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo)

Maker: Anoniem |

| Accession number | DN 130/27 (PK) |

| Credits | Gift Dr A.J. Domela Nieuwenhuis, 1923 |

| Department | Drawings & Prints |

| Acquisition date | 1923 |

| Creation date | in circa 1550-1600 |

| Watermark | none (vV, 8P) |

| Collector | Collector / Adriaan Domela Nieuwenhuis |

| Provenance | (?) J. Mellaart; Dr. Adriaan J. Domela Nieuwenhuis (1850-1935, L.356b), Munich/Rotterdam, donated with his collection in 1923 (Andrea del Sarto) |

| Research |

Show research Italian Drawings 1400-1600 |

| Literature | Cat. 1925, no. 608; Cat. 1927, no. 608 |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Technique |

Highlight

> Painting technique

> Technique

> Material and technique

|

| Geographical origin | Italy > Southern Europe > Europe |

Do you have corrections or additional information about this work? Please, send us a message