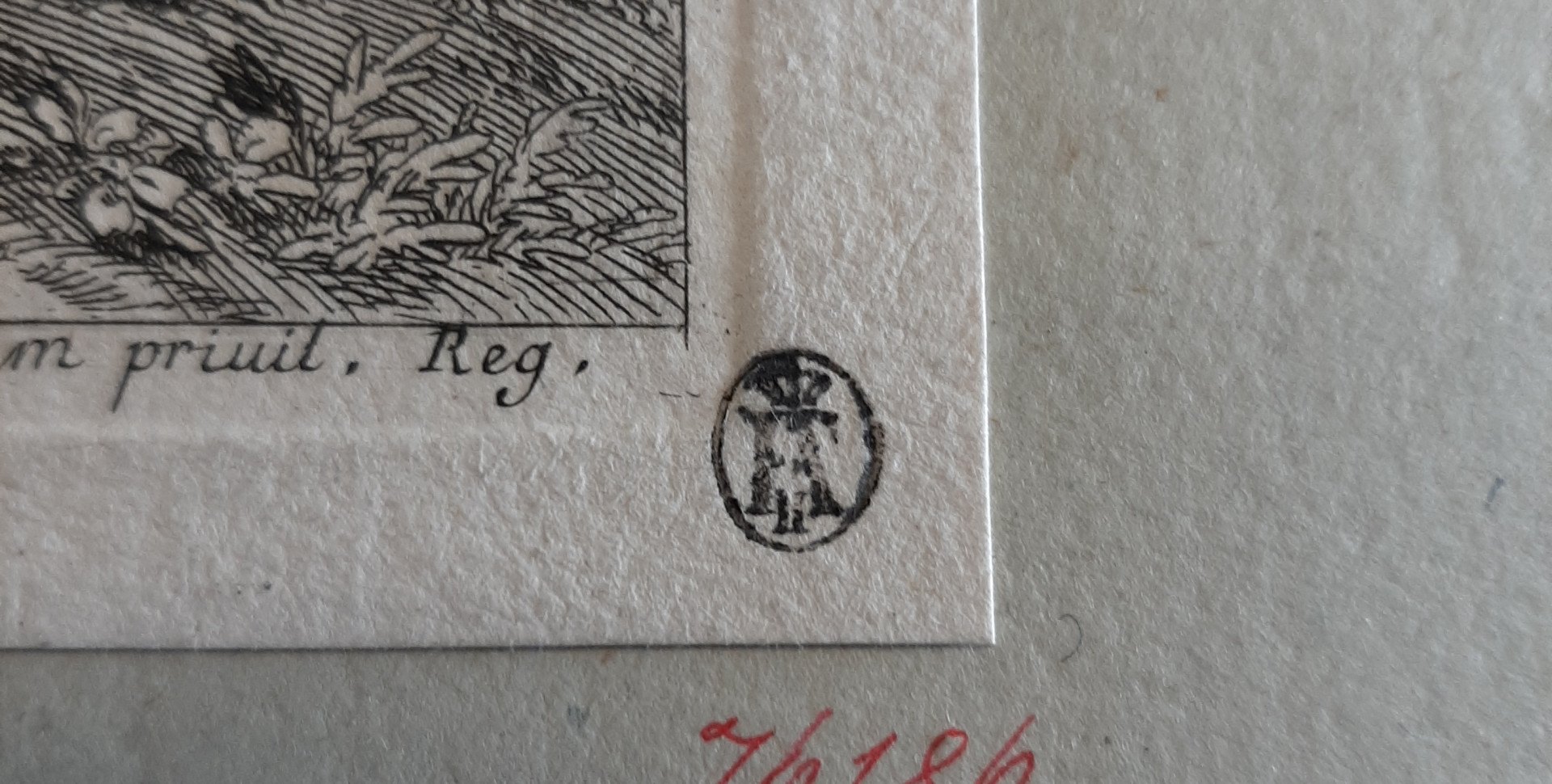

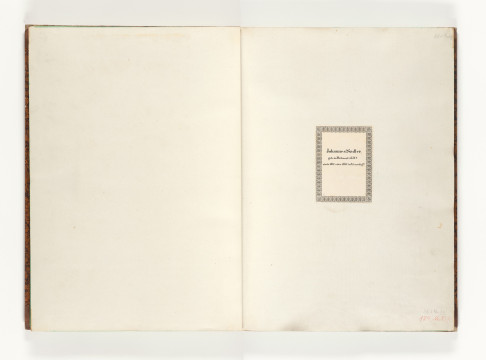

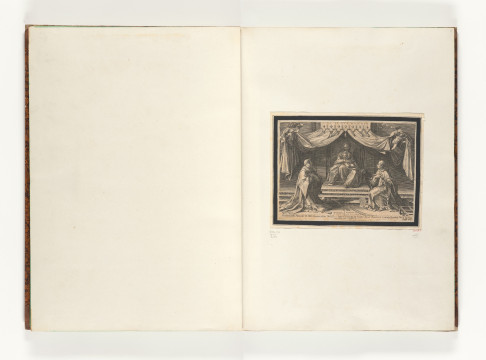

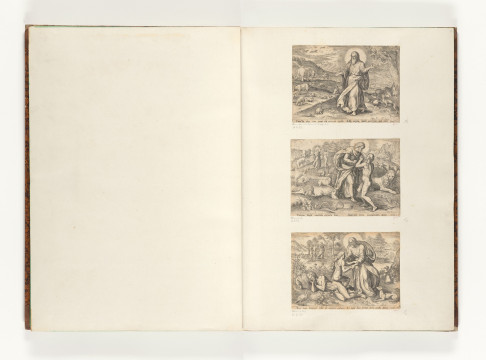

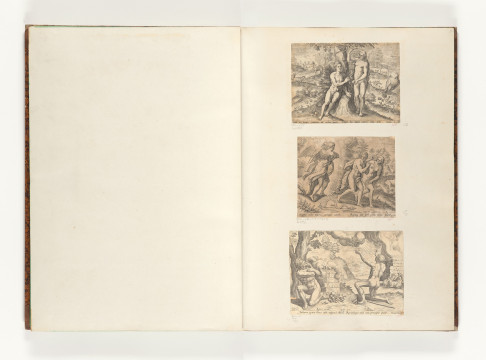

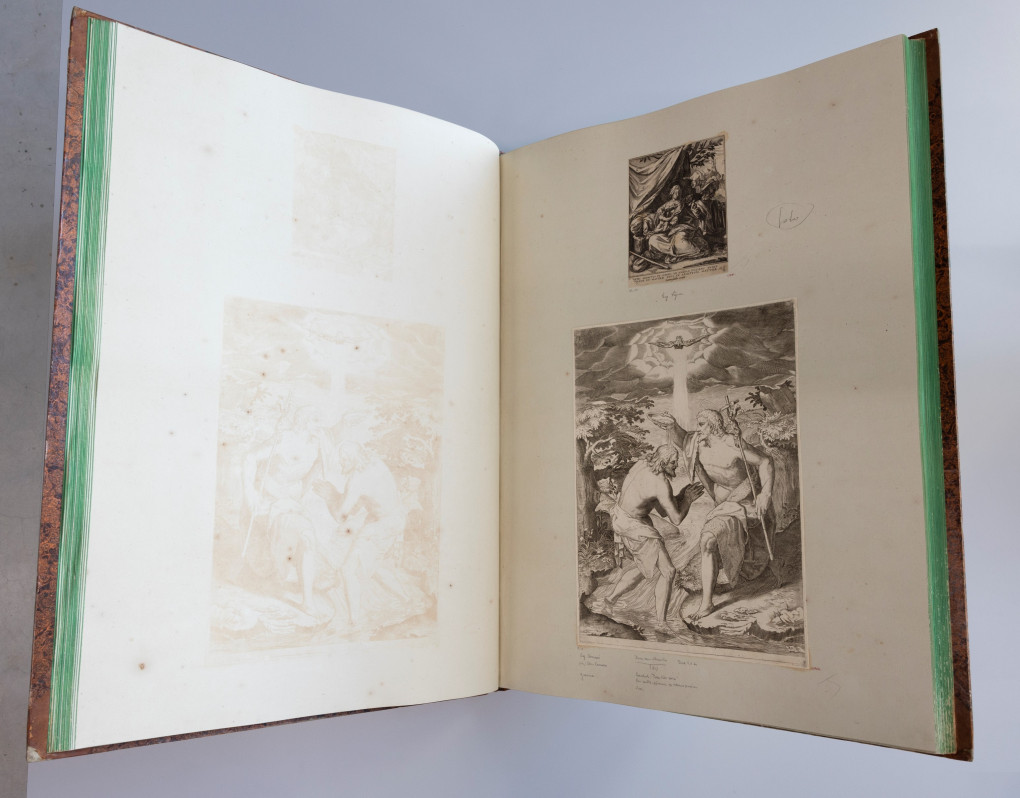

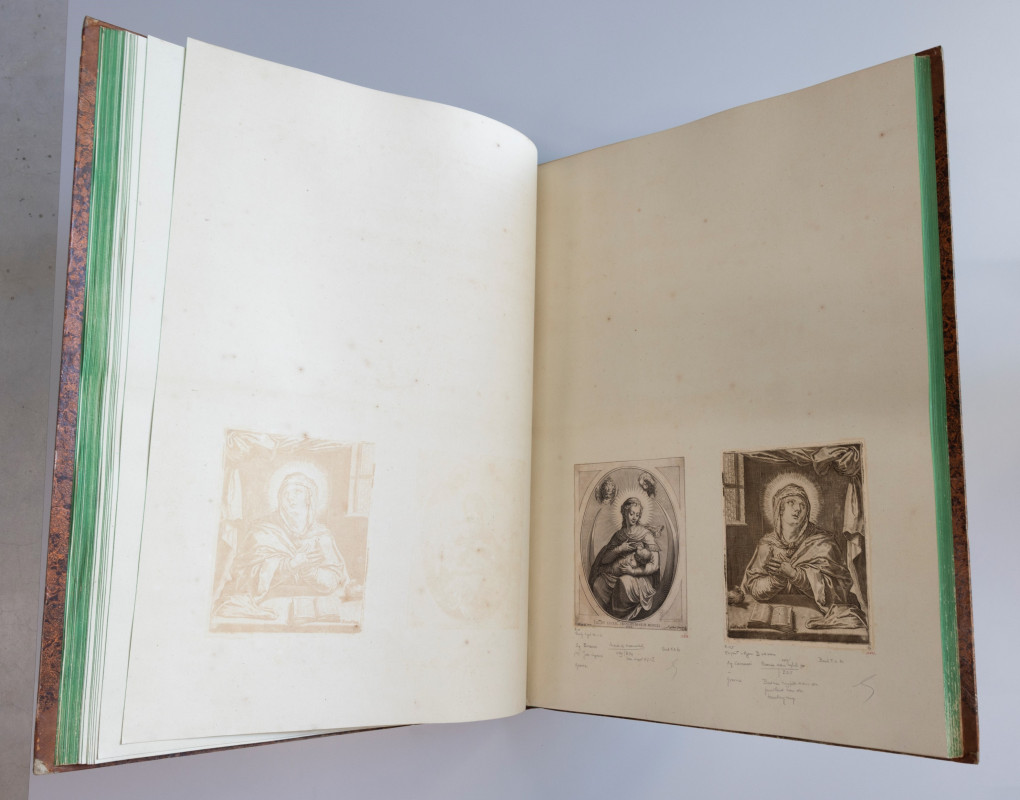

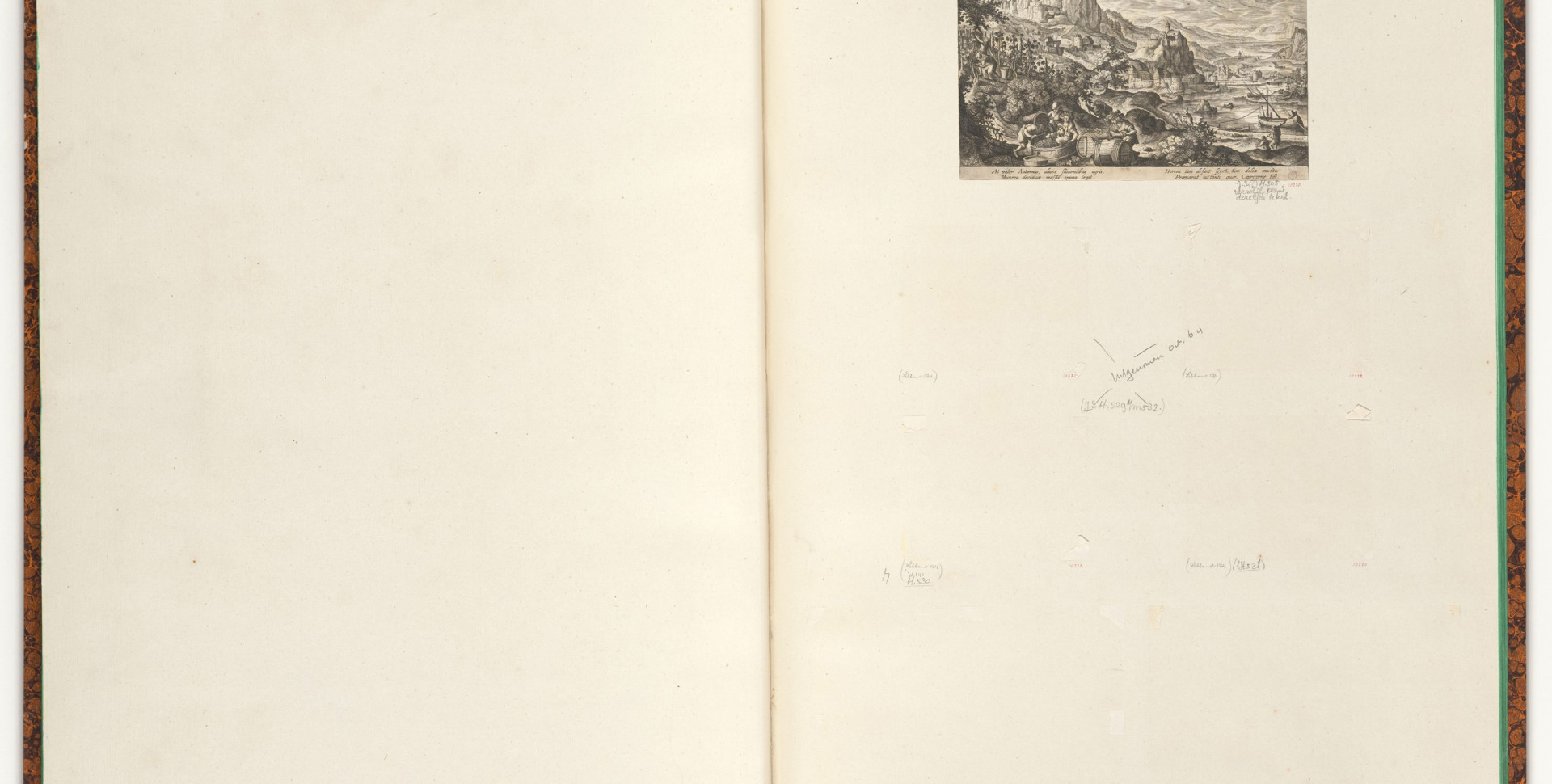

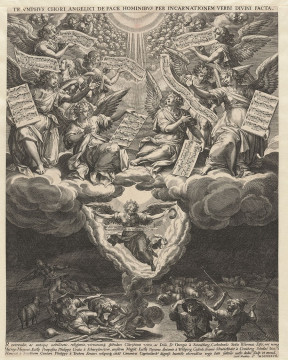

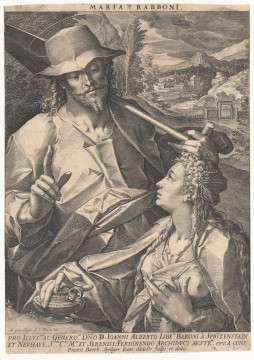

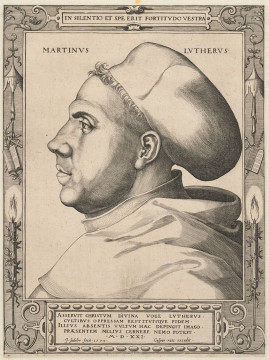

Frederick Augustus II of Saxony (fig. 1) began collecting in 1817. His goal was to put together a complete overview of European art by means of prints – printed images on paper that include woodcuts, engravings, etchings and lithographs. After purchasing these prints at auctions or from dealers he had them mounted in albums. Each print was given a number and a stamp. Since he was reigning as king of Saxony between 1836 and 1854, he would most probably not have been able to do all this himself, so he appointed a curator, Johann Gottfried Abraham Frenzel (1782-1855).

Frenzel writes about the collection in his book 'Die Kupferstichsammlung Friedrich August II. König von Sachsen, beschrieben und mit einem historischen Überblick der Kupfersticher-kunst begleitet' (Leipzig 1854). The way the collection was organized is clear from this catalogue. The albums were arranged by technique, country and artist. At the beginning of the nineteenth century it was customary to classify artists on the basis of national schools, so that prints by Italian printmakers, for instance, would be grouped together. The result was a number of albums for each national school. The arrangement within them was based on each artist in chronological order. An unusual aspect was that Frederick Augustus chose a system based first and foremost on technique. This was different from his contemporaries’ practice.